Some Things About Selenium Still Don’t Add Up

I spend a lot of time thinking about selenium.

It is my favourite element. I have spent more than 15 years, and many millions of dollars, on scientific research and technology development to improve our understanding of it and to develop new water treatment technologies.

Selenium is a required micronutrient. It is also one of the few elements where the line between “necessary” and “harmful” is narrow, context-dependent, and still poorly defined. At elevated concentrations, selenium can be problematic for egg-laying aquatic vertebrates like fish (or salamanders and turtles). In some cases, it can bioaccumulate through the food web into higher-level egg-laying vertebrates such as birds that eat fish.The precise threshold where selenium shifts from acceptable to problematic remains unclear and is likely ecosystem-specific.

In response, policy has largely defaulted to a precautionary posture: less is better. That position is understandable. What is more difficult for me to reconcile are the inconsistencies that have accumulated around it.

After more than 15 years of working as a scientist directly in this space, there are several aspects of selenium policy and regulation that continue to stand out to me as unresolved, and increasingly difficult to justify.

I do not have tidy answers. But the questions themselves matter, and we need more minds thinking on this. So here I go.

Note for clarification: This is written from a lens of selenium regulation and policy in Canada and the US. There are similar challenges ongoing in other countries, yet, at the time of writing, Canada has some of the world’s most stringent policies.

First, there have been orders of magnitude more fish killed in laboratory and field studies to investigate the potential effects of selenium than have been demonstrably harmed by environmental selenium exposure itself. That is not a rhetorical statement, but an empirical one.

We are killing animals to study the possibility of harm at concentrations that, in most real-world settings, have not produced observable ecological damage. At this point, it can be argued that we are killing more animals than we are helping.

Could the means justify the end? Perhaps. Maybe all these animals killed in the name of monitoring will prevent an ecosystem collapse… but in the decades this has been ongoing, that has yet to be seen.

This is not an issue isolated to selenium monitoring, and is a topic of ongoing discussion. Here is a link to a solid peer-reviewed academic article on the topic.

Second, selenium guidelines are often described as being science-based. If that is true, then the way they are applied should be coherent. They are not.

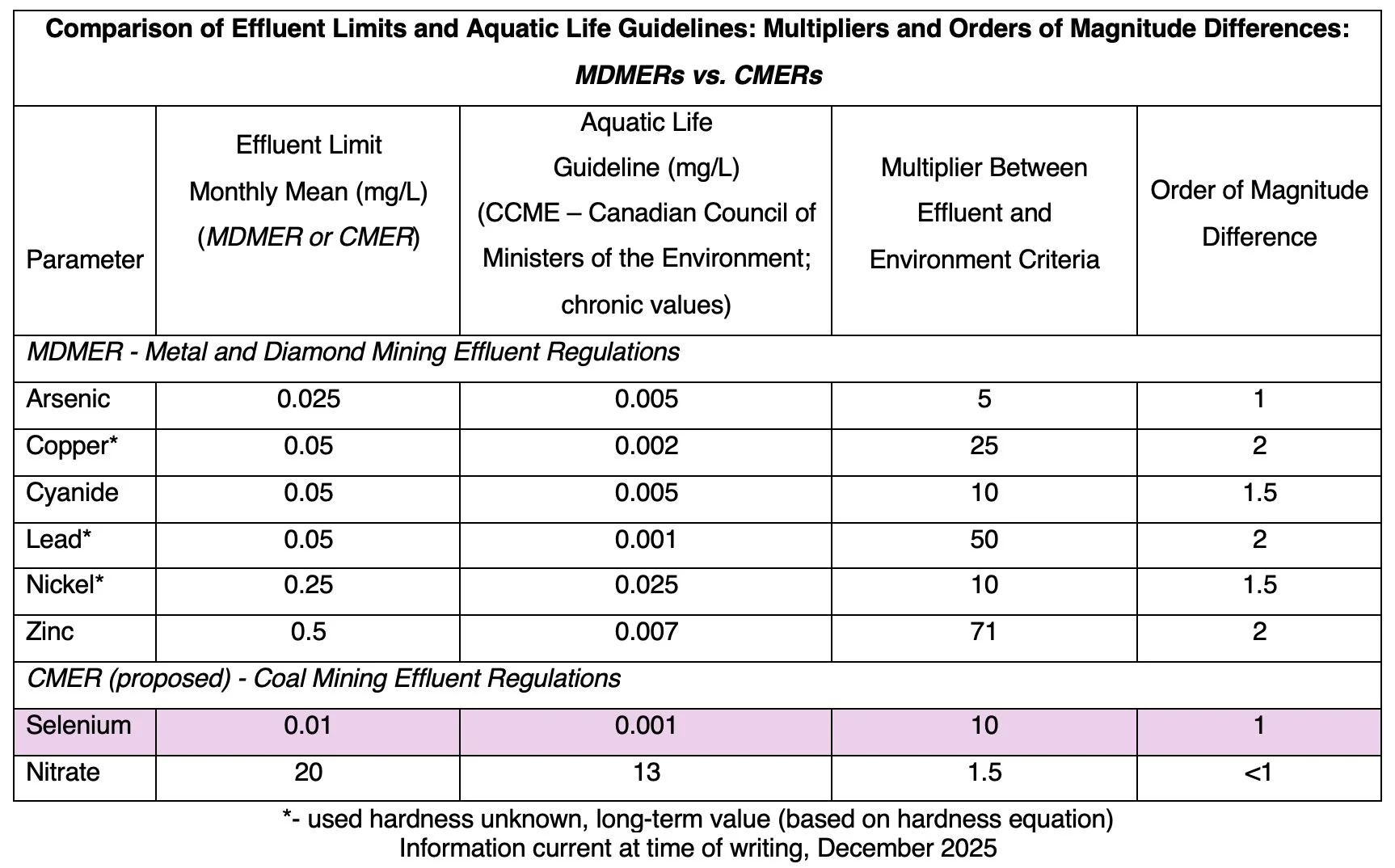

In Canada, mining is regulated more stringently than other industries that release selenium into the environment, and even then, coal mining is treated differently from metal and diamond mining (see table). The topic of regulations and guidelines is covered more in an earlier post here.

The allowable concentrations of selenium and other constituents shown as multipliers and orders of magnitude. The topic of regulations and guidelines is covered more in an earlier post here.

Interestingly, municipalities are generally exempt from comparable scrutiny. Meanwhile, agricultural sectors known to have extremely high selenium discharges (driven in part by the intentional addition of selenium to cattle feed for animal health) are typically not required to monitor selenium at all (let alone manage or treat).

If the mechanism of concern is bioaccumulation through food webs, then regulation should follow exposure pathways, not industry labels. The current framework does not.

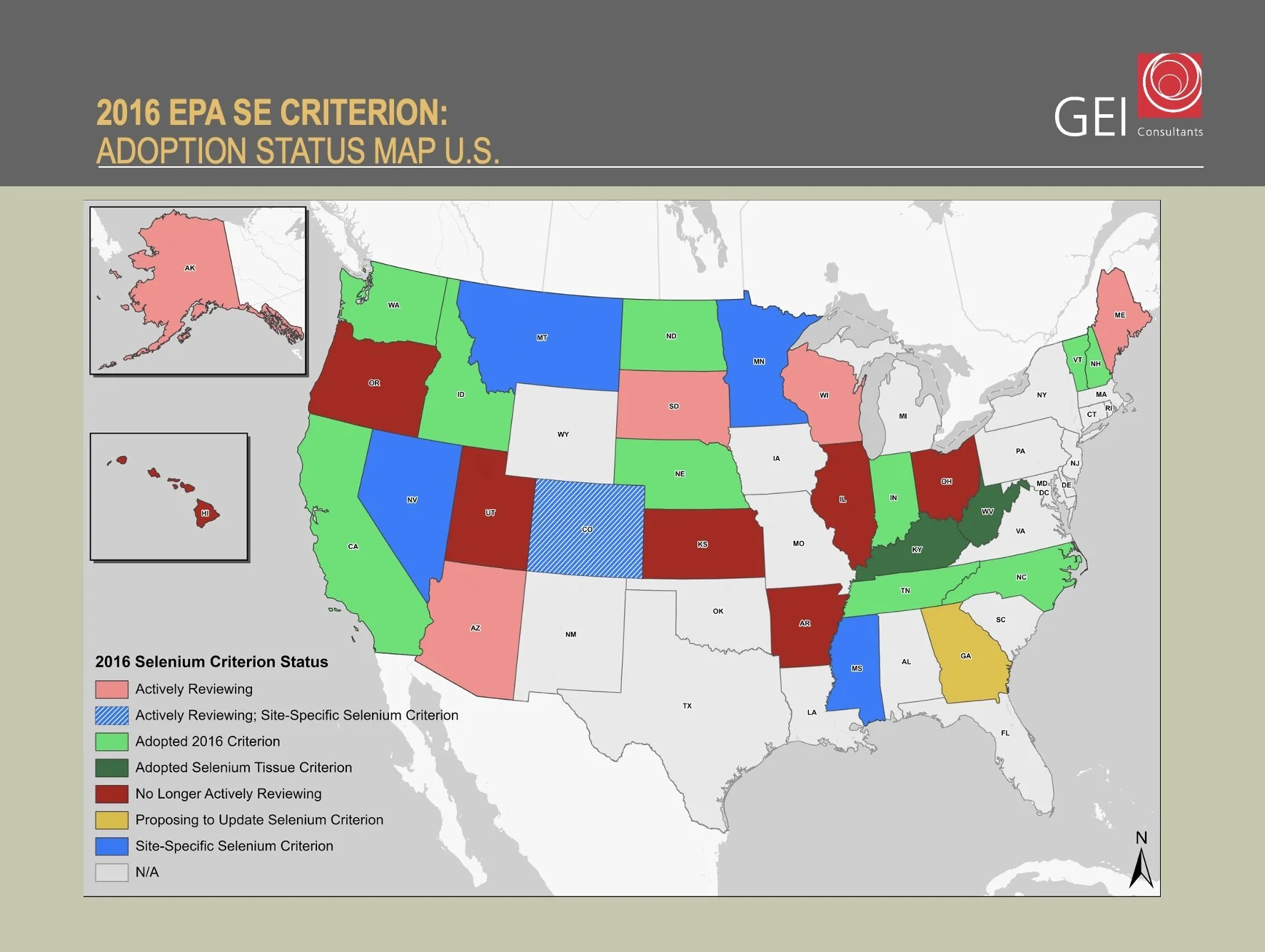

Jurisdictional differences raise additional questions. Some US states consider their guidelines to still be “in development”. Other states choose to disregard selenium water concentrations entirely, arguing that it does not produce meaningful information for bioaccumulation and instead they rely on testing tissue from fish… But this requires killing the fish to assess selenium bioaccumulation, regardless of whether any ecological harm has been observed. However, a highly politicized Canada–U.S. border lake, Lake Koocanusa in Montana, is subject to the most stringent selenium guideline in the U.S., allowing roughly half of the typical U.S. EPA guideline of 1.5 µg/L (note that the U.S. EPA guideline allows for wide-ranging site-specific variation in its application). What could the scientific basis be for a particularly politicized lake to deserve a different selenium guideline than elsewhere?

The map and list above were up to date as of January 2026.

If the science is settled, this variability makes little sense.

If the science is unsettled, the confidence embedded in enforcement is difficult to explain.

In practice, selenium regulation is often driven by lobbying and the reputational risk associated with assigned concentration thresholds, rather than by demonstrated environmental harm.

Third, public narratives around selenium risk have increasingly drifted from evidence.

In Alberta, we have recently seen a rising spread of misinformation that selenium from mining threatens cattle or agriculture. This is despite selenium being purposefully supplemented in cattle feed to improve animal health (much like your own daily multivitamins do). A cow would need to drink on the order of 1,000 litres per day of fully regulatory-compliant mine water to meet its basic selenium nutritional selenium requirement. That is not physically possible. If you follow me on X, you may have seen my posts in follow-up to this article that was written on the topic.

These narratives persist anyway, creating fear that shapes perception and policy long after they have detached from plausibility. If you’d like to read more on the topic of the effects of misinformation around selenium, here is an informative article.

Finally, increasingly stringent selenium limits drive demand for increasingly complex water treatment systems. That demand is rarely framed as the trade-off that it is. This is my area of deep specialty.

Every water treatment process requires chemicals. Every process generates waste. Every system consumes energy. These risks and impacts are real, and they must be weighed against the actual environmental benefit achieved, not against hypothetical or exaggerated harm.

This does not even account for the tens to hundreds of millions of dollars spent annually on individual selenium treatment facilities. Capital and energy devoted to selenium treatment are not available for other contaminants, other ecological stressors, or other forms of environmental protection, which may actually have more impact.

Treatment is not neutral. Over-treatment is not consequence-free.

After decades of research, regulation, and investment, the gaps between evidence, application, and outcome are too large to dismiss as noise.

I wrestle with that reality, because systems that stop reconciling inputs and outputs rarely correct themselves.

The question, then, is how can we have better conversations that actually improve that alignment?

Disclaimer - As always, I have received no compensation for the writing of this article.

Note - links and images were added on December 24th due to incoming requests for references and/or further information. I am not affiliated with any of the consulting firms or people I have referenced, other than the University of Saskatchewan, where I am an alumnus, formerly served as an adjunct professor, and have ongoing collaborations.